The Last Supper: Da Vinci’s Masterpiece, Mystery, and Meaning

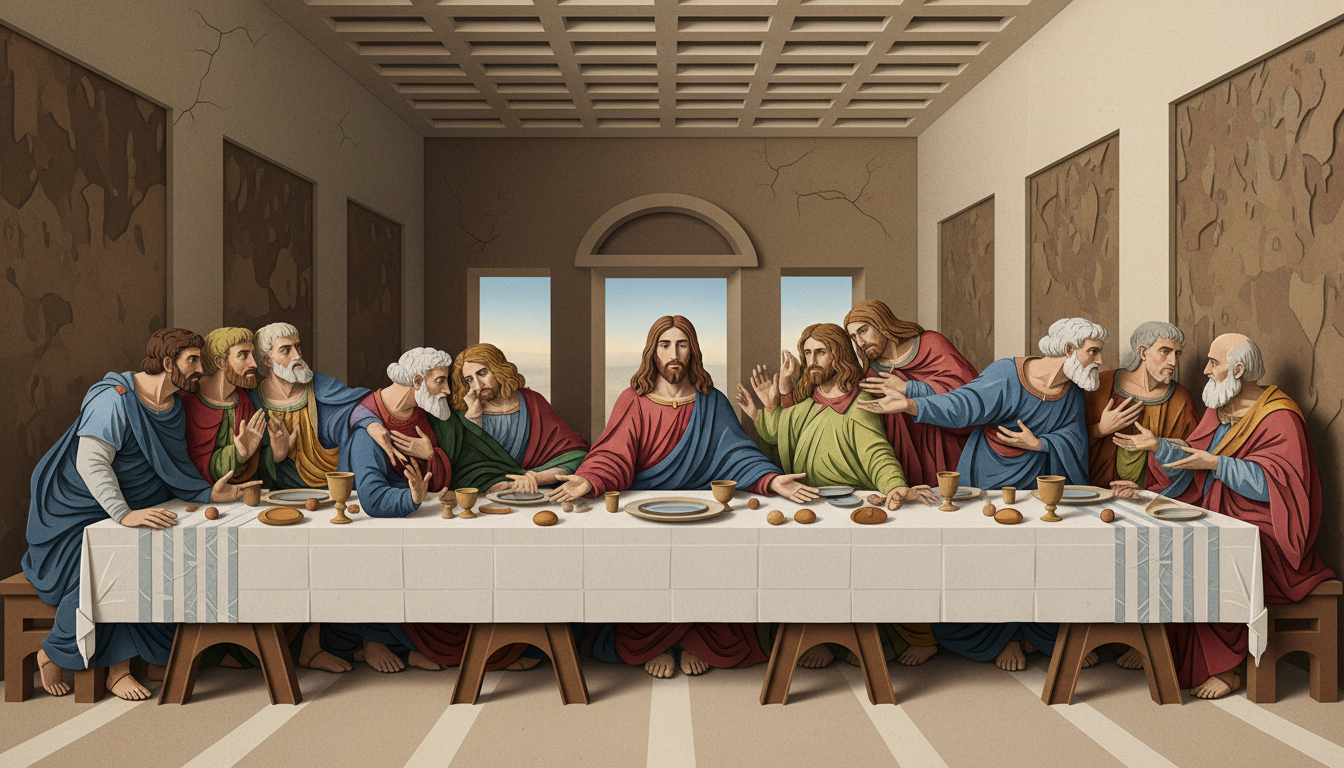

The Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci is one of the most recognisable and discussed images in Western art. Painted between c. 1495 and 1498 for the refectory of the Dominican convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, the mural captures a charged instant: the moment Jesus announces that one of his twelve disciples will betray him. Leonardo transforms a Biblical episode into a study of human psychology, gesture, and controlled chaos.

Historical context and commission

In the 1490s Milan was the court of Ludovico Sforza, the city’s duke and an important patron of the arts. Leonardo, already celebrated for his versatility as a painter, engineer, and scientist, received the commission for the refectory of the convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie. Work on the mural is generally dated to c. 1495–1498. Unlike a traditional fresco, Leonardo painted on the dry plaster using an experimental mixture of tempera and oil, seeking greater subtlety of color and detail. That technical choice, however, made the work unusually vulnerable to deterioration.

Composition and visual strategy

Leonardo arranges the scene with mathematical precision. The painting's dimensions — approximately 460 cm × 880 cm (about 15'1" × 28'10") — make it a monumental presence at the end of the refectory. Leonardo uses linear perspective to direct the viewer’s eye: all the orthogonals converge behind Christ’s head, producing a visual halo and centering him both compositionally and spiritually.

- Grouping: The apostles are clustered in four groups of three, creating rhythms of movement and emotional response.

- Gestures: Each figure reacts differently to Jesus’ announcement—shock, denial, disbelief, and plotting—so that the mural reads like a stage play frozen at its climax.

- Space and light: Leonardo opens the refectory’s painted architecture to receding space, using light to model faces and to unify the scene.

Iconography and symbolic details

Beyond its dramatic staging, The Last Supper is dense with symbolic choices. Leonardo places a simple table laden with food in the foreground and isolates Christ in a serene, triangular composition—an echo of classical stability and a subtle reference to the Holy Trinity. Judas Iscariot is shown leaning back into shadow, clutching a small bag; his position disrupts the line of apostles and signals betrayal. Other details—loaves of bread, spilled salt, and the placement of hands and utensils—have been read as theological cues and as evidence of Leonardo’s interest in quotidian reality.

Interesting anecdote: Leonardo’s insistence on psychological realism led him to study face and hand gestures intensively. He reputedly directed models to enact the scene repeatedly so he could capture authentic expressions of surprise, grief, and anger.

Technique and the conservation saga

Leonardo’s technical innovations produced extraordinary pictorial effects but at a cost. Because he painted on dry plaster and used mixed media rather than buon fresco, the paint film never adhered as well as traditional frescoes. Over centuries the mural suffered environmental damage, earlier restoration attempts, and harmful interventions.

- 17th–19th centuries: Multiple retouchings and changes altered Leonardo’s original surface.

- 1943: Bombing during World War II damaged the convent; protective measures saved the mural from total destruction, though the wall and surrounding structure were harmed.

- 1978–1999: The most extensive modern restoration, led by Pinin Brambilla, aimed to stabilize pigments and remove centuries of overpainting; the project was completed in 1999 and remains controversial among some scholars, who debate how much original paint survives.

Reception, influence, and myths

From the 16th century onward, The Last Supper has been studied, copied, and referenced by artists and thinkers. Its psychological insight influenced High Renaissance and later painters, and its iconic status has made it a frequent subject of scholarly analysis and popular imagination.

In recent decades, popular books and films—most famously Dan Brown’s 2003 novel The Da Vinci Code—sparked sensational theories (for example, speculative claims about Mary Magdalene or hidden codes). Art historians have repeatedly shown that most of these claims are unsupported by documentary or visual evidence. Nonetheless, such stories have increased public fascination and encouraged new audiences to visit Santa Maria delle Grazie.

Where to see it and visitor tips

The mural remains in situ in the refectory of Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan. Because of its fragility, access is strictly controlled: visits are limited to small, timed groups to minimize humidity and temperature changes. If you travel to Milan, book tickets well in advance and expect a short, closely guided visit rather than a long, unstructured viewing. Respect the silence and the room’s original function as a dining hall for monks—this is both a site of art and a sacred space.

Legacy and why it still matters

The Last Supper endures because it marries technical daring with deep humanism. Leonardo turned a Biblical narrative into a study of human emotion and interpersonal dynamics, anticipating modern interests in psychology and narrative. The work’s troubled conservation history also raises urgent questions about how we preserve and interpret masterpieces that sit at the intersection of artistic genius and material fragility.

Final thought: Whether approached as devotional image, scientific experiment, or cultural symbol, The Last Supper invites viewers to stand before a single frozen second that opens onto centuries of devotion, curiosity, and debate.