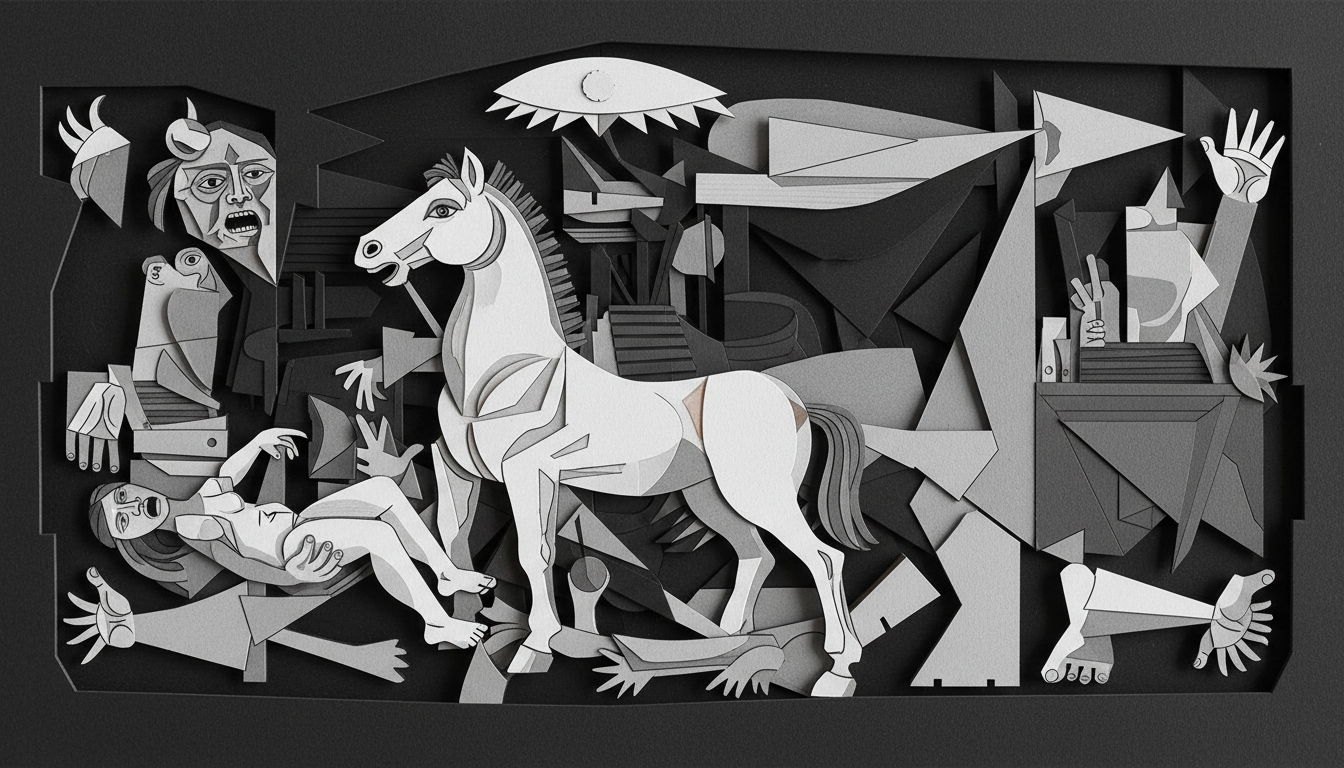

Guernica: Picasso's Monumental 1937 Protest Painting & Legacy

Guernica, painted by Pablo Picasso in 1937, is one of the most powerful and widely recognized images of 20th-century art. Rendered in a dramatic palette of black, white, and gray, the mural-size canvas (approximately 349 cm × 776 cm / 137.4 in × 305.5 in) compresses horror, grief, and political outrage into a compressed, fractured space. Yet beneath its formal daring lies a clear historical impulse: a direct response to the bombing of the Basque town of Guernica on April 26, 1937.

Historical Context: April 26, 1937 and the Spanish Civil War

On April 26, 1937, during the Spanish Civil War, the town of Guernica was bombed from the air in an operation that targeted civilians and caused widespread destruction and loss of life. News reports, photographs, and eyewitness testimony reached artists and intellectuals across Europe. Picasso, living in Paris, was moved to respond. The chaos and moral urgency of the moment — a modern, mechanized form of violence against a civilian population — provided the subject that would shape the painting.

Commission and Creation

The painting was commissioned for the Spanish Republican government's pavilion at the 1937 Paris International Exposition (Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne). Working in his studio in Paris, Picasso produced Guernica between May and June 1937, executing numerous preparatory sketches and studies before composing the final canvas. The resulting work was shipped to Paris for exhibition and, after the exposition, toured internationally as a symbol of the Republican cause and a denunciation of war.

Reading the Imagery: Figures and Symbols

Guernica resists a single, literal meaning — Picasso refused to offer an official explanation — but certain motifs recur in most readings. The painting is crowded with anguished, overlapping figures:

- The Horse: Central and agonized, the horse is often read as the suffering of the civilian population or, more broadly, humanity under attack.

- The Bull: A persistent Picasso motif, the bull can suggest brutality, darkness, or inscrutability; critics debate whether it represents Francoist Spain, a symbol of Spain itself, or a more ancient force.

- The Mother with a Dead Child: One of the most devastating images, this figure evokes traditional iconography of grief and suggests the human cost of violence.

- The Fallen Warrior: At the bottom, a fragmented soldier lies among broken weapons — a collapsing order and failed defense.

- Light and the Electric Bulb: A glaring overhead light (often read as an exploding eye or the mechanical modernity that makes bombing possible) and a lamp held by a woman introduce motifs of exposure, witness, and false illumination.

Rather than illustrate a moment-by-moment narrative, Picasso compresses several responses into a single stage of agony, using distortion, fractured planes, and compressed perspective to convey shock and rupture.

Style and Technique

Although Picasso had been a central figure in the development of Cubism earlier in his career, Guernica is not merely a Cubist exercise. It borrows cubist fragmentation and synthetic composition while drawing on expressionist urgency and the stark immediacy of news photography. The monochrome palette — black, white, and grays — evokes newspaper reports and documentary images of war, lending the painting a public, journalistic tone as well as a funerary austerity.

Reception, Exhibitions, and Political Life

First shown at the Spanish pavilion in Paris in 1937, Guernica immediately entered international circulation as a political artwork. After the Spanish Civil War, Picasso refused to allow the painting to return to Spain while a dictatorship prevailed. For decades it remained abroad as both an artwork and a political statement. It was exhibited widely and became a global emblem against fascism and later against war more generally.

Legacy and Interpretations

Guernica functions on multiple levels: as reportage turned into allegory, as modernist formal innovation turned into moral outrage, and as an artwork that transitioned from a Republican political emblem to an almost universal anti-war icon. Its power stems in part from the fact that it refuses to simplify violence; the painting is noisy, ambivalent, and deliberately opaque — qualities that make it continue to invite interpretation.

Artists, historians, and activists have repeatedly returned to Guernica for inspiration and provocation. Its influence appears in murals, protest art, and popular culture. For many viewers, the painting's most lasting lesson is aesthetic and ethical at once: that modern art can still bear witness to atrocity and mobilize public feeling.

Where It Lives Now and Why It Still Matters

After decades abroad, the painting ultimately returned to Spain and today is housed in Madrid’s Museo Reina Sofía, where millions have seen it in person. Standing before the work, viewers are often struck not only by its scale and formal invention but by its continuing emotional force: its ability to make a historical event remain present, to condense tragedy into a visual language that resists simple closure.

Concluding Thoughts

Guernica endures because it is both exact and enigmatic. It refers to a concrete atrocity — the April 26, 1937 bombing — yet refuses to offer a single lesson. Instead, Picasso gives an image that behaves more like a public cry: complicated, morally urgent, and open to many voices. When we look at it today, we are invited not only to admire its technical audacity but to listen to what it still has to say about war, suffering, and the responsibilities of art.

Suggested further reading: biographies of Picasso, catalogues raisonnés of his work, and exhibition materials from the Museo Reina Sofía provide detailed studies of the preparatory sketches, chronology, and evolving interpretations of Guernica.